St. John's Abbey & University

in Collegeville, Minnesota

St. John's Abbey in

Collegeville, Minnesota is a Benedictine monastery affiliated

with the American Cassinese Congregation.

The Abbey was established following the arrival in the area

of monks from the Saint Vincent Abbey in Latrobe, Pennsylvania

in 1856. Saint John's is the second-largest Benedictine abbey

in the Western Hemisphere, with 164 professed monks. John Klassen,

OSB, currently serves as abbot.

Monks from the Abbey serve parishes in the Diocese of Saint

Cloud and in the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis.

The Abbey's Hill Museum and Manuscript Library houses the world's

largest collection of manuscript images, and will also house

the St. John's Bible, the first completely handwritten and illuminated

Bible to have been commissioned since the invention of the printing

press.

The community operates The Liturgical Press, St. John's University,

and St. John's Preparatory School, all located on the grounds

of St. John's in Collegeville. The grounds also house the Collegeville

Institute of Cultural and Ecumenical Research, the Episcopal

House of Prayer (Diocese of Minnesota), a Minnesota Public Radio

studio, and the Saint John the Baptist Parish Church. The 2500

acre grounds of the Abbey comprise lakes, prairie, and hardwoods

on rolling glacial moraine, and has been designated as a natural

arboretum.

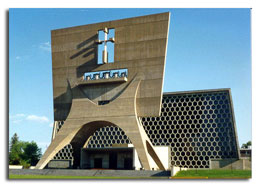

The Abbey is the location of a number of structures designed

by the modernist architect Marcel Breuer. The Abbey Church with

its banner bell tower is one of his most well-known works. --

From Wikipedia

The

North Facade and Bell Banner of the Abbey Church

THE BELLS - On the vigil of Christmas, 1989 the

present bells were dedicated. These bells replace the original

bells that were

first installed in the former abbey church in 1897 and moved

to this church in 1960. The five bells were produced by Petit & Fritzen

bell foundry in Aarle-Rixtel, Holland and purchased through I.

T. Verdin Company of Cincinnati, Ohio... The largest bell weighs

8,030 pounds while the smallest bell weighs 1,683 pounds... The

bells are dedicated to the Holy Trinity, Blessed Virgin Mary,

Guardian Angels, Saint John the Baptist and Saint Benedict.

The Abbey Church of Saint John the Baptist

The Abbey Church of Saint John the Baptist is the place of worship

for the monastic community of Saint John's Abbey. The monastic

community celebrates the Eucharist and the Liturgy of the Hours

here each day. In addition, the church is the home of Saint John

the Baptist Parish and is the primary place of worship for the

Saint John's University community... The Abbey Church is one

of the masterpieces of architect Marcel Breuer.

The Heritage

Edition is the limited-edition, full-size reproduction of The

Saint John’s Bible. The Heritage Edition presents

an opportunity for select subscribers to personally experience

this extraordinary manuscript. The Saint John’s Bible

Web Site

In the 8th Century, near what are now Scotland

and England, Benedictine monastic scribes created a Bible that

today is one

of the longest surviving monumental manuscripts in the Western

world... Nearly 1,300 years later, renowned calligrapher Donald

Jackson approached the Benedictine monks of Saint John’s

University and Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota, with his life-long

dream: to create the first handwritten, illuminated bible commissioned

since the invention of the printing press. The Saint John’s

Bible uses ancient materials and techniques to create a contemporary

masterpiece that brings the Word of God to life for the contemporary

world.

A Perfect Script - By The Reverend Christopher Calderhead

Donald Jackson assembled a team of skilled scribes

to write The Saint John’s Bible. They expected to have

an exemplar of the script, a pattern or model they could follow.

But there

was no exemplar. They arrived at the Scriptorium to find a script

in development, a work in flux. This was not just an omission.

There was a method in it.

The calligraphers came together in February 2000

in order to form a working team. This visit has been dubbed ‘the Master

Class’. Everything else was put to one side as Donald and

his scribes studied the script together. The whole process of

writing was examined, tested, pulled apart, and put back together

again. The script would gel along with the group.

“It’s not a question of copying a shape,” Donald

said, “but adopting a shape as your own child—nurturing

it—making it your own. It should be open for the scribes

to do what they’d hoped they’d do with it.”

The challenge he was setting them was enormous. What was this

script he presented to them? It was a complex creation.

Brian Simpson described it. “It was more different from

other scripts than I thought. I looked at it at first and said, ‘Oh,

it’s a rounded italic.’ But it’s not. It is

difficult.” Sue Hufton had a stab at describing it. “It

is not conventional. Not roundhand, italic, or foundational.

I got myself in a muddle early on with these terms. It’s

not even a mixture of these terms. It’s not easily defined.

It’s to do with the movement of the pen. It’s rounded,

but not a wide round. It’s based on an oval rather than

on a circle. The action is similar to round letterforms, and

to cursive, italic, whatever.”

This was a script which challenged the easy classification the

scribes might have been used to. I asked Sally Mae to describe

it: what was the pen angle; what were the proportions?

“It’s not to do with that.” None of the classic

calligrapher’s vocabulary applied. “No pen angle,

no x-height, no exemplars. At the end of the day, I had to throw

all that out the window. You have to trust yourself, and you

have trust DJ.” Sue echoed Sally: “I was presented

with a script that in a funny kind of way made me set aside everything

I knew about letter forms, the relationships between letters—put

to one side all my preconceptions about letterforms. And yet,

this is the thing—I needed every scrap of knowledge and

experience I could draw from.”

The notes for the master class appear alarmingly

casual. A block of eighteen lines of Bible script appears at

the top of the first

page. It is a loose, even casual, version of the script. It is

dotted with small annotations. Below this, enlarged letters and

parts of letters give evidence of a detailed discussion of the

Bible script. These, too, are marked with small checks and xs.

This is not an exemplar. It looks like the kind of thing you

see on a blackboard in school after a long and complicated lecture.

Donald told me he had to stop doing the large demonstration writing;

it altered the motion of the pen, so didn’t reflect the

subtleties of the writing at the smaller scale of the actual

text.

Sue remarked, “I would not have done it this way. This

is what I am required to do. But then it becomes my own.” She

paused for a moment before correcting herself. “No. It

becomes ours.”

The team aspect quickly became important. Sue

said, “When

we go down there, we feel part of a team, even if we haven’t

met all the team members—especially the illuminators. We

refine the script together. Donald doesn’t have any one

set way. You want security of an exemplar. But it’s good

we never had one. The evolution has been allowed to happen.”

Now that they’ve been writing for the better part of two

years, Brian said to me, “Two years in, and we’re

just beginning to understand the script. It feels better, it

looks better.”

Sue agreed. “It amazed me how much we’ve been pushed

to our limits. ”Brian said on their last visit to the Scriptorium, “It

got quite exciting—we laid our pages all out, like a book—we

could see the thing as a whole. It came to life. The weight,

texture, appearance of the script all held together. It was all

from the same book. Personality is important. It does not stifle

personality. It’s a harmony: The individual struggles fade

away.”

When they step back from their work, they can

enjoy what they have made. I asked him about how the ink sat

on the page. “The

ink dries well. It’s almost shiny. You can see that it

stands just proud on the vellum.” He paused for a moment. “It’s

a lovely thing,” he said with a sigh.

|