|

Soul Searching;

By:

JANET KINOSIAN - The LA Times, Tuesday,

June 2, 1998

They

are children. But they're under lock and key for crimes

including murder. Authorities are grasping for new methods

to reach them--techniques that attempt to tap into the souls

of these young inmates.;

It's

a shocking image--even to the accustomed eye.

Fourteen

children, the oldest of whom is 11, are lined up, marching

with hands clasped tight behind their backs at Central Juvenile

Hall in East Los Angeles. The youngest child, 8 years old,

is outfitted in bright orange prison garb, signifying he

is a high-risk violent offender, a category that includes

murder, assault and armed robbery.

The

usual prison shackles are absent--those are saved for when

the kids are transported in and out of the detention center--but

spiritually and emotionally, the shackles are there for

many.

It's

the spiritual realm these young offenders are being helped

with today, as a team of Buddhist monks and teachers spends

an hour teaching the children how to meditate and how meditation

might help those who will need to survive extended time

in the California prison system.

In

this overburdened, underfunded juvenile detention system,

officials have turned to a relatively new youth-detention

concept: teaching spiritual practices. They hope these skills

will help heal the emotional scars of these young inmates

and help them learn to manage lives that are clearly out

of control.

Noy

Russell heads Central Juvenile Hall's Excel program, which

since 1993 has offered classes in "life skills," such as

drug and AIDS/HIV awareness, to incarcerated children. He

says officials were desperate for new approaches. As both

state and federal law prohibit the mixing of religion and

classroom instruction in public institutions, many of the

spiritual practices are viewed as "life management" skills.

"We

were almost literally at our wit's end," Russell says, noting

that there are about 670 children, ages 8 to 18 (about 630

boys and 40 girls) housed at the East L.A. facility.

"Most

kids here feel society has written them off, and the kids

were also feeling warehoused. That resulted in high assaults,

both between the kids and between the kids and staff," Russell

says. "We were willing to look anywhere and everywhere for

some help."

Where

California juvenile justice officials have looked, in part,

is to spiritual techniques like yoga, Buddhist meditation,

Native American sweat lodges and Tibetan sand mandala ceremonies,

martial arts practices like akido and tai chi, and psychological

strategies such as keeping journals and consciousness-raising

groups. One Buddhist monk even teaches meditation principles

along with how to overcome suffering through blues harmonica.

Most techniques have been in place in various facilities

for about a year.

"Without

question, the introduction of these ideas has been better

than even I had hoped," Russell says. "The kids felt heard,

seen and listened to, and I think they responded like anyone

would respond to caring: They became less angry." He claims

the rise in assaults and in gang activity has been dramatically

curbed in the last eight months since the programs were

instituted, and says officials are currently compiling a

report with firm data.

William

Burkert, superintendent of Central Juvenile Hall until last

week (he has been promoted to bureau chief of auxiliary

services for the Los Angeles County Probation Department),

says he promotes the idea of these volunteers "as long as

they don't preach their own personal gospel and they're

not here to convert anybody. Sadly, not a whole lot of people

want to work steadily with these kids." He calls the spiritual

programs at Central "a positive priority. We'll keep the

doors open until someone proves to me they should be closed."

"If

you went inside the heads of these kids, it's like 12 fire

alarms going off in an insane asylum," says David Eaton,

a deputy probation officer at L.A. County's Camp Kilpatrick

in Malibu, where Los Angeles Buddhist monk Rev. Kusala

teaches the blues

harmonica class

every Tuesday. Kilpatrick is one of 13 juvenile detention

camps owned and run by the county.

"Anything

that can help these kids clear and calm their minds, even

for a few minutes, is great," Eaton says. "I've noticed

a discernible difference in a whole lot of kids."

Talk

about spirituality was a bit much for preteen boys who assembled

on one recent day to learn how to meditate from Kusala and

Michele Benzamin-Masuda, an instructor with the Jizo Project

from L.A.'s Ordinary Dharma Center.

"Hey,

is this some kind of psychic gig?" one 10-year-old shouts.

Benzamin-Masuda

continues steadily with her teaching, asking the boys to

try and focus on their breathing.

"Shoot,

I might as well have stayed in my room and done voodoo,"

yells a 9-year-old, running from the room.

Benzamin-Masuda

rings a bell and asks the children to focus now on the center

of the room. The kids begin to bombard the brown-robed monk

with questions.

One

boy says of meditation, "It's kind of like a dream. You

know, like Martin Luther King. Everybody followed him because

he said he had a dream, and he thought he knew what his

dream was and everybody followed him sort of wanting and

hoping the dream was true."

The

children settle down and begin to practice meditating.

"Part

of the trouble is that these kids' defense systems are very

high to begin with," says Kusala, who is with the International

Buddhist Meditation Center in Los Angeles, which has been

instrumental in bringing Buddhist spiritual practices into

the juvenile halls. "Remember, people often had deceptive

motives when they paid any attention to them. Some classes

are more chaotic than others, and some are smooth as silk."

He

says it's generally the older boys--15 and up--"who realize

a little better what their reality is and know they need

help and seem to catch on very quickly."

A

visit to a meditation class in the "KL" group (boys 16 to

18 who are standing trial for murder) finds students who

are attentive, intelligent and polite.

"When

I stress about my case, and my situation, and the things

that have happened, I can focus on my breathing and get

a respite," says a 17-year-old boy who has been in the KL

unit for a year. "Sometimes not having any words is better."

Javier

Stauring, Central's Catholic chaplin, thinks the silence

and meditative practices have a more profound result for

troubled youngsters "rather than just having supportive

people who show up to listen to their problems. The discoveries

these kids are making about themselves is amazing. Our hope

is that these discoveries will remain, and I think the silence

has helped a lot. They don't get a lot of silence in this

institution."

Critics

believe such notions are heartfelt but misguided.

"Of

course there's nothing intrinsically wrong in trying to

teach kids some spiritual values and practices," says David

Altschuler, a Johns Hopkins principal research scientist

who has done extensive juvenile delinquency, crime and prevention

research at the Hopkins Institute for Policy Studies in

Baltimore. "But to say in and of itself it's any great new

workable approach, in my opinion, is naive.

"Teaching

kids the bagpipes would likely have a similar effect," he

says. "It's not necessarily what is being taught, but the

fact that the children are feeling attended to."

Altschuler

says spiritual teaching, if used as a means to begin to

tackle some of the major issues that brought these children

to corrections institutions--such as serious family dysfunction,

drug dealing and violent peer pressure--may help.

"But

on its own, I have my serious doubts," he says. "My question

here is, where's your evidence?"

He

claims the "obvious answer" is more and better clinical

staff supervision that consistently "deals directly with

these kids."

But

with cutbacks in clinical supervision--according to Russell,

the ratio of clinicians to children at Central has gone

from 1 to 150 in 1993 to 1 to 350 today--addressing the

day-to-day problems of the inmates can't wait for research

to catch up.

Of

the 15 state juvenile facilities in California, three have

Native American sweat lodges. At the California Youth Authority's

correctional facility near Camarillo recently, several dozen

young people experienced the ancient ceremony, which symbolizes

a return to Mother Earth's womb to gain strength, guidance,

purification and healing.

For

90 minutes (divided into four rounds: one dedicated to the

participants, another to their relatives, a third to their

surroundings and the last to their ancestors), the inmates

sing, beat drums, pray and sweat.

"Kids

will either get their anger out or act it out," says Josie

Salinas, a Youth Authority counselor who was instrumental

in opening the lodge at the facility. "This is an ancient

and peaceful way to purify what's imbalanced."

As

a group of teenage girls crawls out of the lodge, one assesses

the experience.

"I

know this isn't going to change the fact that I'm in prison,

but it helps me realize some reasons I got here," she says.

"It helps me think more clearly, and that's not something

I'm very good at."

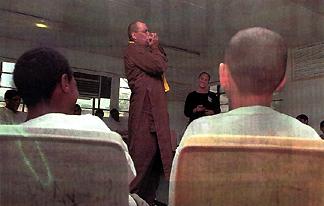

Rev.

Kusala spending some time in Central Juvenile Hall

with Buddhist volunteer Michele

Benzamin-Masuda.

Playing some blues

for

the guys in Juvenile hall with

volunteer Michele Benzamin-Masuda looking on.

Accepting

the “Good Samaritan of the Year” award with

friend and Excel coordinator Mr. Noy Russell.

“Guilty”

by Silvia - Los Angeles, Central Juvenile Hall

Two days after my conviction they found me guilty of 1st

degree murder,

conspiracy and robbery, which carries a life sentence without

parole. And the

horrible thing about this is that I did not do it. They

convicted me without any

evidence. I feel sad and real bad because they took my whole

life away. I had

dreams of being somebody. I had dreams I wanted to accomplish.

Now I don’t

have anything. All the things I wanted to do and the person

I wanted to be died

on April 7, 1997.

I’m really hurt. I don’t know how I’m going

to tell my parents that their little

girl has been found guilty of all charges. And it’s

really hard for me because I’m

still a little girl. I was only sixteen years and nineteen

days old at the time of the

crime. Now I’m eighteen years and two days old and

I still feel as if I’m only

sixteen. Why did they take my life, dreams, hopes and family

away from me?

Don’t they know I could have been somebody? I could

have been a famous

doctor, lawyer, teacher, or anything I wanted to be, but

now I can only be an

inmate for the rest of my life.

Oh, how it hurts. It was my birthday the day they decided

to take my life

away. Why, why? That is the question I ask myself. Why did

they find me guilty?

God, answer my question, please. Why did you allow this

to happen to me?

Sometimes I lie on my bed and I cry, then I laugh and say

to myself, God, why

do you want me alive, what’s the purpose? If I going

to suffer all my life, I’d

rather be dead than go through this. Why was I ever born?

I guess I was born to

suffer.

But the one thing I want to let them know, and for you to

know, before

they lock my door and throw away the key, is that I was

only sixteen, in love,

confused and stupid, and I did not commit this murder. So

even if they convicted

me of it, now you know I did not do it. And if you don’t

believe me, it’s okay

because at least God and I know the truth.

**********************

I

hardly

cry. I haven’t cried for a long time, but today I shed

some tears as

my friend brought memories of my trial and the last day

when I got convicted.

That was the worst day of my incarceration. I cried like

a baby all night long.

I remember my friend Osuna bringing me a cup of water. I

showered right

after I came from court and me and Osuna stood inside the

bathroom crying.

She was telling me she wanted to do some of my time. Then

we had to come out

of the bathroom because they had cake and ice cream. It

was my birthday, but I

was to sad to celebrate.

Now I’m trying to erase that day. It felt good after

I cried, but throughout

the next day I kept crying as people asked what happened

in court. I couldn’t

answer their questions but through my tears they knew what

had happened. Now

I’m trying to heal from the day the jury found me guilty

and trying to prepare for

my sentencing day. I know then I will cry a lot. But for

now, my tears are dry.

The LA Times... Tuesday, June 22, 1999

A

Night to Remember!

L.A.'s

most notorious youth lockup is an unlikely place for a

prom. But Saturday evening, That's just what it was.

By

SAM BRUCHEY, Times Staff Writer

They

call this place the crossroads. It's where children pass

the final

of their youth in bright orange uniforms and 10-foot-by-12-foot

rooms that lock

from the outside; and where the only reminders of life on

the

"outs" are murals of such heroes as Oscar De La Hoya

and Florence Griffith Joyner on the concrete a barbed wire

walls.

Until

now.

On

Saturday afternoon, the Los Angeles Central

Juvenile Hall did what no other juvenile hall in the

county has ever done: It held a prom.

The event was intended to give 73 youths--ages 16 to

19--a reward for earning their high school diplomas,

something Central officials say minors in

incarceration are altogether unaccustomed to receiving.

"It gives them an opportunity to feel proud," said

Dr. Jennifer Hartman, assistant superintendent of the

Los Angeles County Office of Education.

"It lets them feel human again."

But

some Central staff members worried that too much

freedom, such as allowing direct contact between male

and female minors--something Central ordinarily

forbids--could lead to problems.

"We held a mixer last week and talked to the boys

about treating the young ladies with respect," said

Kenyaata Watkins, one of the coordinators of the prom.

"Once that went well, it alleviated qualms we had about

[the event]."

"Some people don't think the kids deserve a night

like this," said Shirley Alexander, Central's

superintendent. "But you've got to do more than stick

kids in cells if you want them to rehabilitate and return

to society."

Many

Violent, Repeat Offenders

Most won't be returning to society any time soon. The

facility, which holds 619 minors, making it the

largest in Los Angeles county, is also the most

notorious. Central houses more violent and repeat

offenders in Los Angeles than any other facility.

According to Central officials, all the boys and most

of the girls attending the prom fall into that category.

Yet

the prom, dubbed "Stepping Into the Next

Millennium," went off without a hitch.

Beginning at 4 p.m. on a clear and breezy afternoon

inside Central's vast interior grass courtyard, 45

nervous boys in black tuxedos, cuff links and stiff

new shoes escorted 28 girls, who wore glittering

gowns and walked unsteadily in high heels, to the

gymnasium for four hours of dining and dancing.

All of the clothing for the event was donated by

local merchants. Beauticians volunteered their time

to style the girls' hair and apply makeup.

"They said they would come but only to do one girl,"

said Maria Alvarez, who sat on the prom committee.

"But once they got here, forget about it. They were

so touched, they didn't leave until every girl was done."

Outside

the gym, couples stopped momentarily for a

photograph in front of their choice of donated luxury

car--Mercedes, Rolls-Royce or stretch limousine--to

create the lasting impression of having arrived in style.

The

gym was festooned with black, white and gold

balloons, drawings and paper decorations. Appetizer

arrangements included an apple juice fountain, mounds

of cheese and crackers, and ice sculptures filled

with fresh fruit. Dinner included chicken, baked

potato and ice cream with strawberries and cookies

for dessert.

"For

a while I forgot that I'm incarcerated," said

Martin, 17, from East Los Angeles, whose trial is set

to begin later this summer. "This is the closest I'll ever

get to a

prom. For others, however, the best part was just being

able to move about without restriction.

Juveniles at Central typically march in highly

structured groups, called movements. They are led by

trained detention officers and are required to walk

in silence, facing forward with their hands clasped

behind their back.

Ordinary

activities such as using the bathroom,

making a phone call or writing a letter are

privileges at Central that require permission.

"When I got here tonight," said David, a wiry

17-year-old who has been incarcerated for more than a

year, "I wasn't sure if I needed to raise my hand to

get up. I was afraid to walk around."

Security officers were worried that the freedom might

lead to fights or even attempted escapes.

"You wouldn't know it tonight," said Duane Leet, who

was in charge of security for the prom, "but a lot of

these kids are aligned with hard-core street gangs

and would be going at it on any other night."

Still, full precautions were taken. The event was

staffed with 10 security officers, each carrying

pepper spray. Tables were arranged in a semicircle,

with minors seated farthest from the exits. And,

throughout the night, minors were discouraged from

clustering in groups or milling around the doors.

Good

Behavior Was 'A Pride Issue'

The

evening passed without the slightest ruffle,

because, most said, nobody wanted to ruin a night this special.

"It's a pride issue," said Corey, 18, who was

selected prom king on the basis of his essay about

leaving the past behind. He and prom queen Sylvia,

19, shared the first dance. "We wanted to prove to

everyone that if they showed faith in us to do good,

then that's what we were going to do."

An encouraging attitude from hard-core offenders.

"Some of these kids are looking at 25-years-to-life

sentences," said Marty Fontain, a teacher at

Central's school. "For them to finish their degrees

in spite of all the distractions in a place like this

is extraordinary."

One

of those distractions is a transfer to someplace

worse, such as the California Youth Authority or San

Quentin, which comes when a juvenile turns 19. So for

many at Central, education takes on an entirely

different meaning.

In prison, a GED can mean a safer yard assignment

with offenders who are less violent. It can also mean

greater store privileges, or better jobs, including

clerical, library or even tutorial work.

Mostly, though, education becomes a source of pride.

"I passed my GED as soon as I got here so I could do

something for my mother," said Charlie, 17, who

described himself as a "very high-risk offender."

"Taking classes has also eased the pain of being

locked up and taken my mind off court."

In the last several years, the number of minors

earning their high school diplomas or GEDs in Los

Angeles juvenile halls has increased dramatically.

This year, 998 graduated from high school; nearly 600

more than in 1994, according to Larry Springer,

director of Juvenile Court and Community Schools in Los

Angeles.

Springer

attributes the rise, in large part, to the

increased number of GED test centers. Several years

ago, minors could only take the GED at one juvenile

facility in the county. Today the test is offered

once a month at every juvenile facility.

Those at Central, however, give credit to the

school's strong curriculum, year-round classes and

favorable student-to-teacher ratio of 17 to 1.

Students, they say, routinely overcome reading

deficiencies measured at three or four years beneath grade

level. And this year's reward for that progress may be

incentive for future inmates hoping for a prom of

their own, although officials have not yet committed

to future dances.

After

the prom, detention officers bent the rules and

allowed the boys to talk as they marched back to

their units. They laughed about the dancing, the

music and those who missed out by not graduating.

"These kids are going to be talking about this night

for a long time," said Joe Sills, a senior detention

service officer, as he pointed to the shadowed

figures of other boys staring out from their rooms at

the returning group. "They'll make sure the other

kids know how good this was."

"I'm not saying they wouldn't go out and make the

same mistakes again if they were let out today,"

Sills said. "But tonight they weren't murderers,

thieves, thugs, rapists and all the rest of that

madness. Tonight they were kids."

Also See:

Buddhism

and Social Action An Exploration...Ken

Jones

Violence

and Disruption in Society...Elizabeth

J. Harris

|